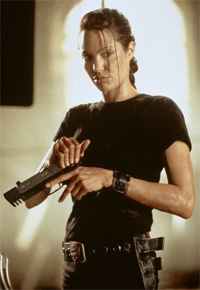

Danger Gal: Lara Croft/The Gaze: Terry Sheridan

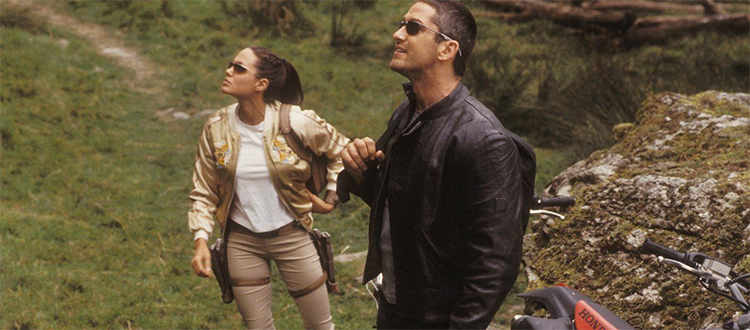

This week’s Danger Gal and Female Gaze installments are related: Tomb Raider 2’s Lara Croft and her love interest/partner/sidekick Terry Sheridan.

Gerard Butler’s character of Sheridan is, much to many a female’s delight, objectified but not emasculated. In fact, the Female Gaze celebrates ultra-masculinity while at the same time valuing the character’s emotions.

Gerard Butler’s character of Sheridan is, much to many a female’s delight, objectified but not emasculated. In fact, the Female Gaze celebrates ultra-masculinity while at the same time valuing the character’s emotions.

Sheridan first appears in the movie when Croft rescues him from prison. In this first meeting he’s working out by doing pull-ups from the ceiling and is dressed in less clothing than Lara.

Throughout the movie, Sheridan attempts several times to reconnect with Croft, and his appeals play more to her emotions than to remembered sexual chemistry. The former is more often employed by female characters, the latter by “macho” males. For example, take the following exchange:

Sheridan: So, where do I fit in?

Croft: What do you mean? You’re the guide.

Sheridan: I mean, when you think back on the vast scheme of your hugely adventurous life… where do I fit in? Was I the love of your life, or just another bump on the road? Was I time well spent? Four months? More good than bad? Come on, it had to be more than that, am I right?

Croft: You’re right. It was five months.

At one point in the movie, Croft watches Sheridan undress from afar in a scene that obviously is meant to appeal to a female audience and depicts a woman who clearly has a libido, has in the past acted on that libido and has not been penalized for such actions.

The gender reversal is complete when Sheridan makes his final move to try to get back their former physical relationship when both half-naked, Croft handcuffs Sheridan to a metal bed frame on the floor. Sheridan’s response to this development? “Not quite what I had in mind, but. . . OK.” Sheridan is desperate to reconnect with Croft on any terms.

Despite this gender role reversal, male audiences have flocked to Croft films, including those male audiences who loved the original video game where Croft was clad in far less. In the game, Croft is much more objectified, but in the films that objectification has been turned on its head — and yet the men still love it. Wired’s Clive Thompson points out that part of Croft’s appeal is certainly the cheesecake factor, but it’s more complicated:

I think young boy gamers loved Lara for reasons that were considerably stranger. They weren’t just ogling her: They were identifying with her. Playing the role of a hot, sexy woman in peril — surrounded by violence on all sides — was, unexpectedly, a totally electric experience for young guys.

Thompson cites Carol Clover’s The Final Girl theory wherein the last “man” standing in a thrasher film is a girl, and at that point in the movie the audience ethos switches from cheering on the villain to rooting for the “final girl” to triumph. Male audiences are putting themselves in a girl’s shoes.

While the Croft character is certainly not the feminist ideal and she is objectified in various ways, in other ways she subverts stereotypes. Skye over at Heroine Content points out that:

She [Croft] is treated so much better than women are usually treated in these films. Lara is never called “bitch” or “that woman” by her enemies. She is called “Croft” or “Lady Croft.” They don’t strip her and torture her. They don’t threaten her with sexualized violence. She’s playing on even ground with men, and she gets the same respect and the same threats they would receive.

Croft has self-determination. She does what she wants, when she wants it and no one questions her right to that self-determination based on her gender. Movieland’s Ann Morrow points out that

… [with] Jolie’s super-serious interpretation of the action vixen—Lara’s feminism comes across as having been earned at a price, and she exudes just enough ethical grit to make The Cradle of Life just a little more involving than sheer escapism. Even if it is the kind of movie that Lady Croft wouldn’t deign to waste her time on.

In all but one (her father) of Croft’s relationships with men, she is in charge. As Charlotte Starlet points out in her essay Women in action movies: Empowered role models or chicks with guns?, Croft wrests control from the Illuminati cult of the first movie, her butler’s bids to get her to wear a dress, to her “dominant relationship” over both Sheridan and Alex, an archaeologist from the first Tomb Raider movie. In fact, while I’ve concentrated here on the Female Gaze elements of the second movie, the first movie involves a shower scene depicting Alex West, portrayed by Daniel Craig of later 007 fame.

In the first few seconds of this scene it’s unclear who is in the shower and the obvious assumption is that it’s Croft, but it turns out to not only be an example of the Female Gaze of the audience, but more blatantly a chance for Croft to ogle the movie male love interest:

[Alex West steps out of the shower and finds Lara there. She looks down at his crotch, smiling]

Croft: Always a pleasure.

[Croft leaves]

West: And now a *cold* shower.

When Alex walks out of the shower, a table in the foreground conceals his crotch from the audience, but not to Croft. A maid enters, sees him and shrieks, but Croft has no such hysterical reaction. She’s not afraid of anything, including such an obvious example of maleness.

I agree with Starlet when she says that “[T]his dominant female/submissive male contradicts Mulvey’s theory of the male as active/female passive; however, one must note that a dominant, sexy female is a popular male fantasy.” Angelina Jolie took the poster girl for pseudo-feminism and reconstituted her with a dimension not expected in an action film. Sure, watching Tomb Raider 1 or 2 won’t change your world view, but it’s a fun two hours not only mostly devoid of misogynistic stereotypes, but with a stronger kick-ass heroine than I anticipated and a bit of sex appeal for both female and male viewers.

Okay, you used lots of big words and brainpower for this post, but all I can say is “HUBBA HUBBA.” WOO HOO for the Female Gaze! Can’t wait to see more of posts about it. Mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm…..

Now, who did she choose? After she killed Terry, did she get together with Alex, or what? 😉

I guess we’ll have to wait for movie #3 to find out, though I doubt Daniel Craig will take time away from James Bond to hang out with Lara Croft. 🙂

Maybe the writers will find a suitable third option.

Yeah, you´re right. But I also think Lara doesn´t really need a man. I guess she´s better off alone. But I like the idea of her and Terry or Alex…;-)